Getting fiscal: Analyst for La Jolla cityhood effort goes inside the numbers of local property taxes

Urban economist Richard Berkson tells the La Jolla Shores Association how tax revenue is typically allocated and says ‘your property tax bill won’t change’ if La Jolla becomes its own city.

When La Jolla homeowners pay their property taxes, much of it goes to public schools, some goes to the city of San Diego and the rest is divided among county entities.

The La Jolla Shores Association learned details of the allocations during a presentation by urban economist Richard Berkson at its virtual meeting July 12.

Berkson and his firm, Berkson Associates, are assisting the Association for the City of La Jolla in preparing a fiscal analysis to explore whether La Jolla could secede from San Diego and incorporate as an independent city.

Berkson also did a 2005 fiscal impact study for a different group seeking La Jolla cityhood when he worked for Economic & Planning Systems.

“I’ve been working over 30 years preparing budget forecasts, fiscal analyses, analyzing government reorganizations [and] incorporation studies for the formation of new cities,” he said. “Estimating property taxes is a key element to all of those projects.”

Who pays property taxes and how much?

Homeowners pay 1 percent of the assessed value of their properties in property taxes since the approval of Proposition 13 in 1978.

Assessed value “is basically what you paid for your property with various adjustments,” Berkson said.

Smaller amounts called “overrides” are added, he said, such as voter-approved assessments and bonds that fund things like San Diego Zoo maintenance, school district projects, vector control and more.

Get the La Jolla Light weekly in your inbox

News, features and sports about La Jolla, every Thursday for free

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the La Jolla Light.

Unless you recently purchased your property, its assessed value is not equal to its market value, Berkson said.

“The assessed value can increase no more than 2 percent a year or at the rate of inflation if inflation happens to be less than 2 percent,” he said.

A reassessment of value — such as what might happen after a sale or remodel — can trigger an adjustment in property tax.

Other adjustments also may be employed, like an exemption of $7,000 off the assessed value, Berkson said.

How property taxes are divided

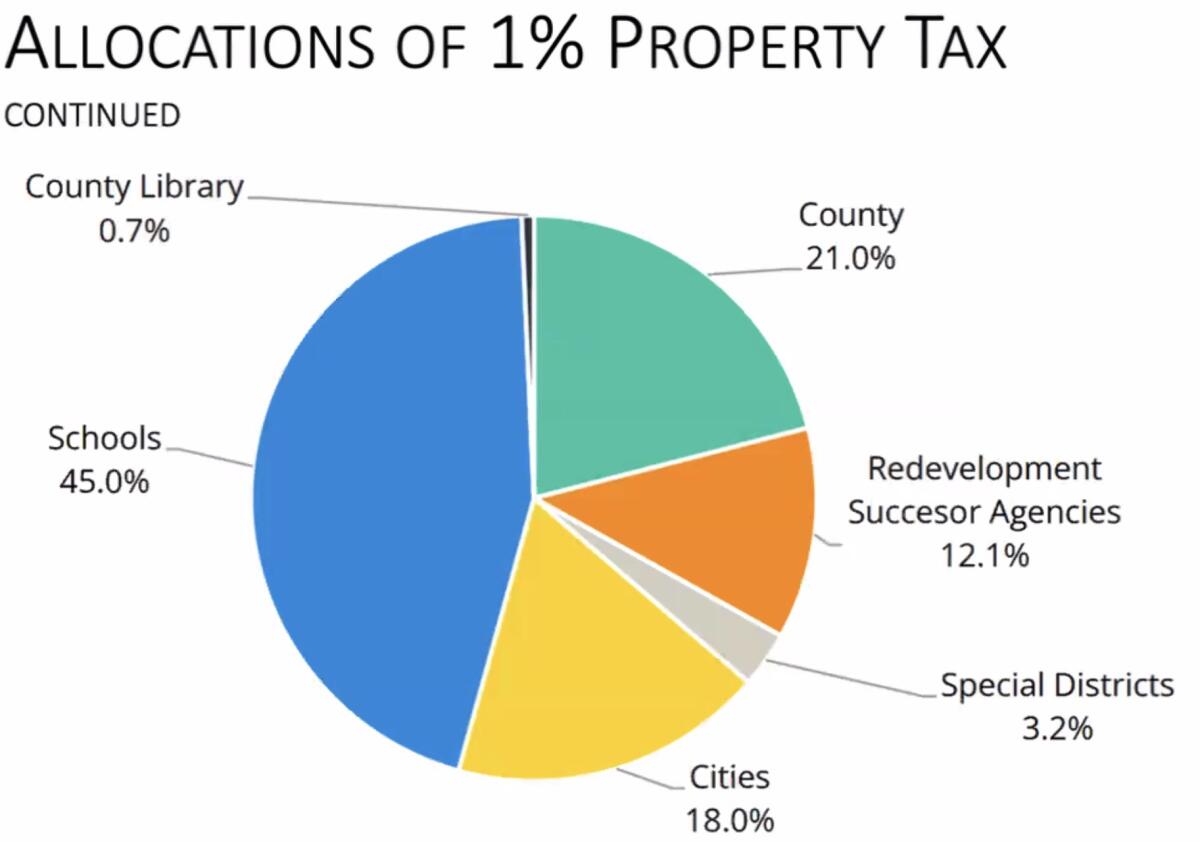

Though many people think the city keeps most of its homeowners’ property taxes, it actually gets about 18 percent in a typical example of property tax division that Berkson shared.

The example is “close to what I understand the city of San Diego will get,” he said.

The largest share — 45 percent — goes to schools. The county receives 21 percent.

“That’s fairly typical,” Berkson said.

Each of those entities — plus others that receive portions of the rest — is listed in a “tax rate area.” Counties include hundreds of tax rate areas, each “a set of taxing agencies that serve that geographic area,” he said.

An auditor adds up all the allocations from each tax rate area, which determines how much a particular agency receives.

How San Diego spends its share

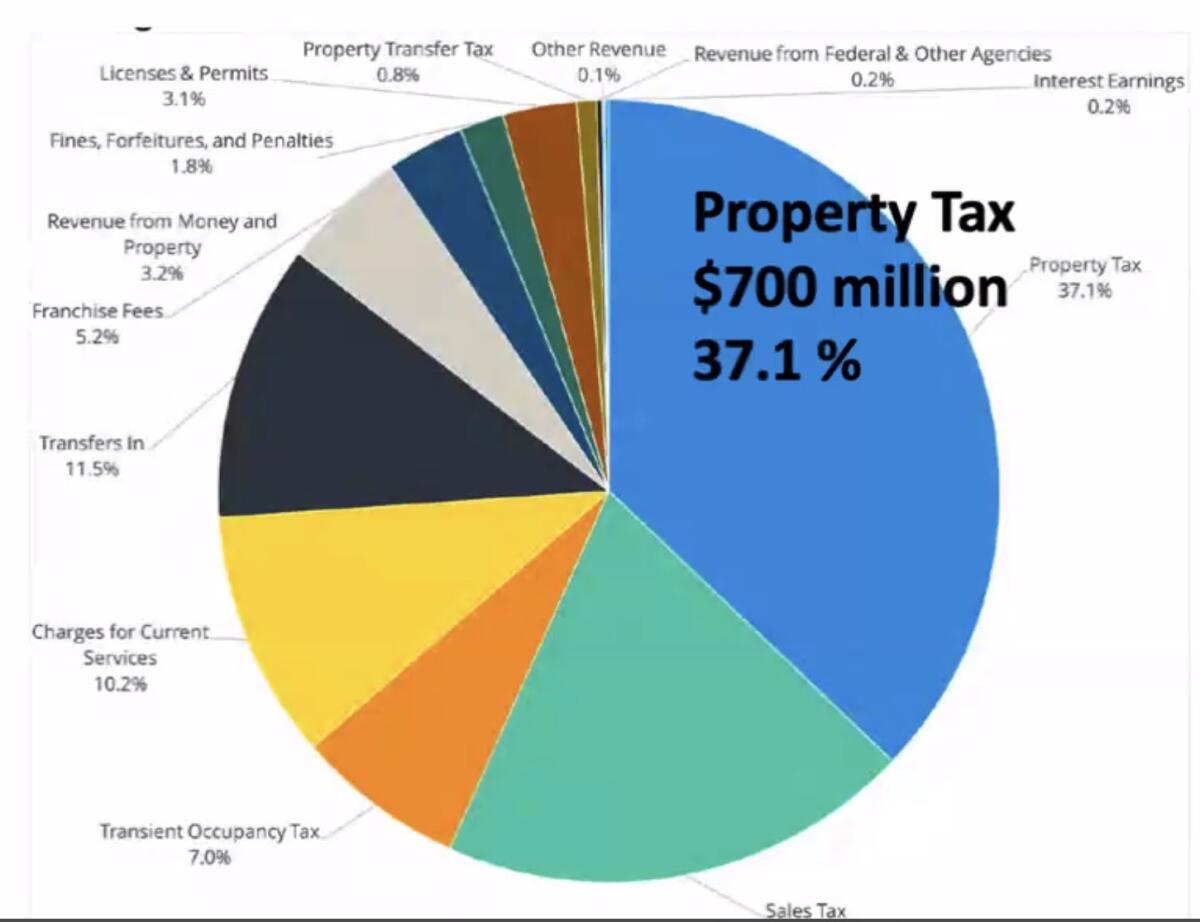

The portion of property taxes the city of San Diego receives makes up 37 percent of its nearly $2 billion general fund, Berkson said.

“It’s obviously a very key part of funding public services,” he said. Other revenue sources are sales and hotel taxes and various fees for services.

Police use the largest chunk; other services are fire, parks and recreation, libraries and more.

Though growth in assessed value is normally capped at 2 percent per year, reassessments after property resales “can provide a large bump in total property taxes” the city receives; it often grows 4-6 percent, Berkson said.

Such a bump depends on the strength of the real estate market and whether property values have increased and homes are being bought and sold frequently.

“Five to 15 percent of property might sell in a given year,” Berkson said.

Incorporation impacts

La Jolla still faces a long road to independence — the next step is evaluating Berkson’s feasibility study, which may be completed this summer.

But if it does succeed in becoming a city, there will be no property tax impact on homeowners, Berkson said. “You will still just pay your 1 percent.”

Though there are various formulas that govern adjustments to how taxes are allocated among the entities that receive them, “your property tax bill won’t change.” ◆

Get the La Jolla Light weekly in your inbox

News, features and sports about La Jolla, every Thursday for free

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the La Jolla Light.